At The Floating Hospital, health equity is in our DNA

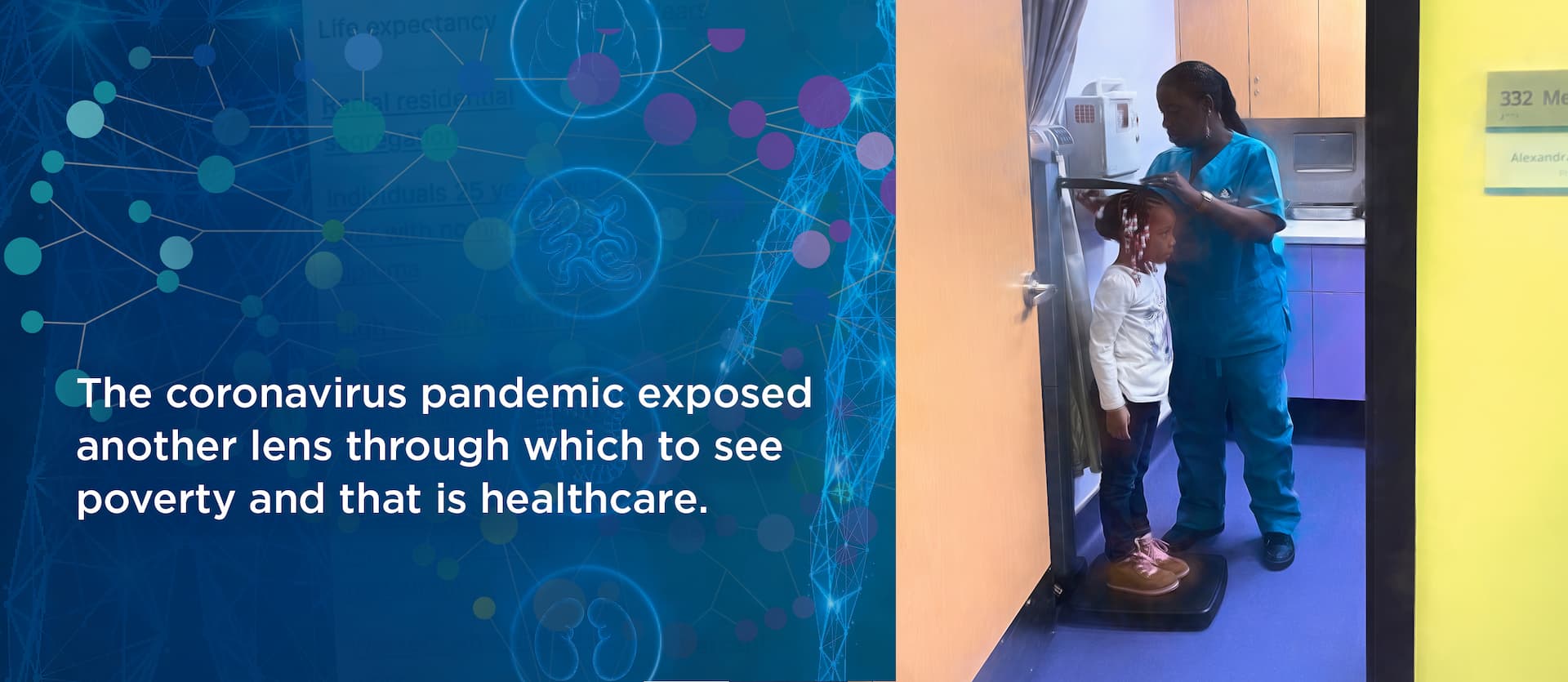

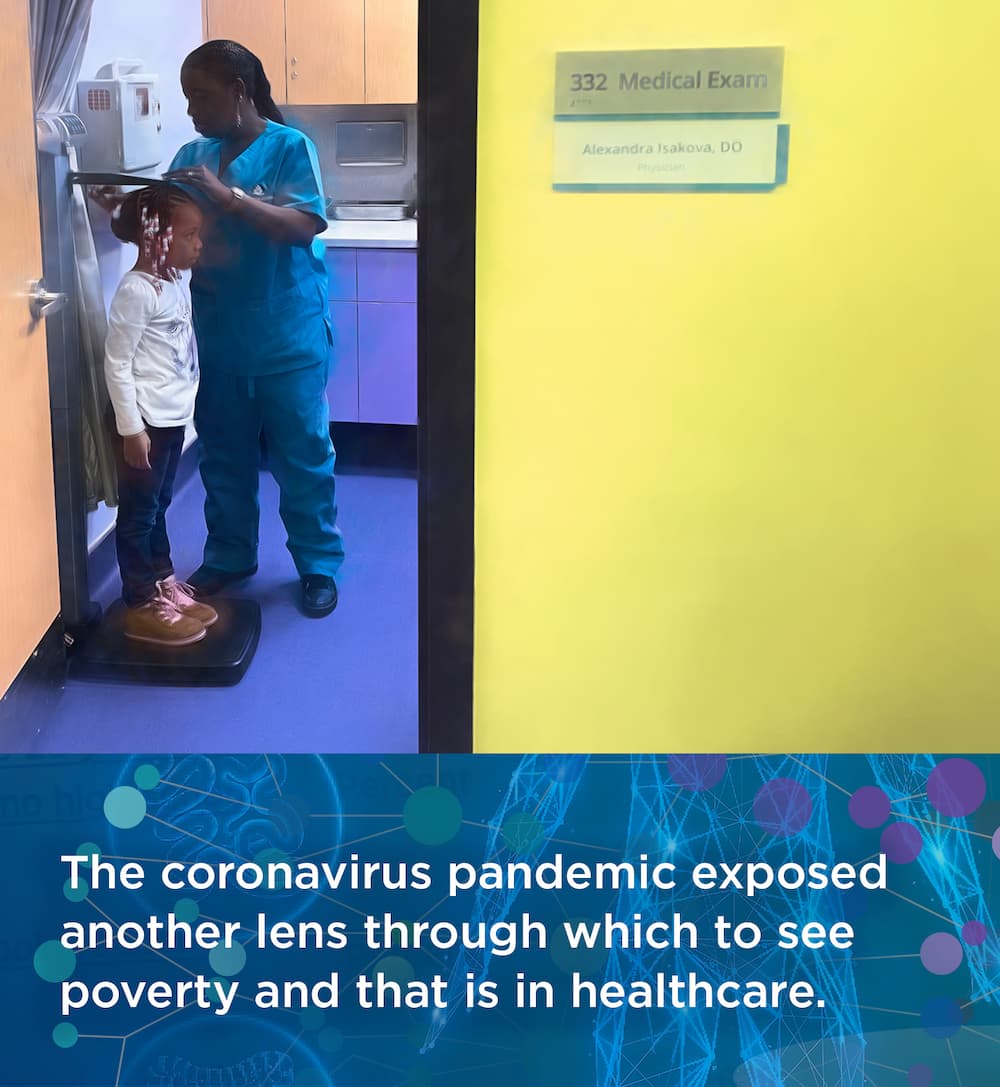

One of the most topical conversations coming out of the coronavirus pandemic is how a public health crisis lifted the veil off inequities suffered by the poorest Americans and, overwhelmingly, in Brown and Black communities.

The New York City Department of Health reported in the first year of the pandemic, Latinx and Black New Yorkers were up to two times more likely than white New Yorkers to report difficulty in paying for housing and utility bills, and unable to afford public transportation and groceries. Black New Yorkers (51% ) were more likely than white New Yorkers (43%) to report job loss or reduced working hours during the pandemic.

But the coronavirus pandemic exposed another lens through which to see poverty, and that is in healthcare. The pandemic laid bare those inequities—again, with people of color disproportionately affected by the triumvirate of comorbidities, malnutrition and food insecurity.

Such inequalities have existed for years, but in an interview with The New Yorker magazine, Nancy Krieger, professor of social epidemiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said “the virus “is pulling a thread that is showing … the very different conditions in which we live because of social structures that are inequitable, both within the United States and between countries. By pulling the thread, it’s revealing patterns that have long been known in public health.”

It’s something The Floating Hospital has known since its beginnings in 1866, when it was founded to provide healthcare and relief to New York City’s most disadvantaged families. At the time, that was the diverse wave of immigrants who needed healthcare and more—a bath, a healthy meal and education on food sanitation and nutrition. Those issues remain, 156 years later says Floating Hospital president Sean Granahan.

“These conditions— all related to malnutrition and most prevalent in the impoverished patients we serve—created the most vulnerable class of Covid victims and sufferers. They helped create a disparate infection rate and severity rate among Covid patients,” he said.

Families living in homeless shelters are further hindered by a lack of control over their food sources. They rely on shelter kitchens and free food programs, but such pre-made meals tend to be high in fat, sugar and salt, which exacerbate underlying poor health conditions. And for those living in high-density housing projects or shelters in urban centers—environments of constant and overwhelming car emissions—higher asthma rates are another layer in the health-equity divide. The result is a perfect storm of health maladies that fuels the severity of Covid symptoms.

So when faced with the global health pandemic, TFH used its 156-plus years of experience in breaking down barriers to meet the needs of patients where they were—from transporting them from shelter to clinic for care to having a staff that speaks 24 languages and so much more in between.

Partnerships in the health-equity fight have been vital, as Medicaid and other government funding falls short in the “more than healthcare” arena says Granahan.

“Private funding has been critical in bridging the gap between what traditional Medicaid pays for and being able to provide these types of programs,” he said, citing foundation grants and individual donations that support the clinic’s patient shuttle and its new life-skills program, the latter of which helps link families to food sources, housing opportunities, social services, education and childcare.

“Health education and helping families outside of the normal healthcare model is critical to dealing with public health issues like the pandemic,” says Granahan. “We put an emphasis on understanding how and what they eat and put in their bodies ultimately affects their health—I think that’s really the crux of it.”

Educating families and especially involving children as change agents, he says, can be a great equalizer in the uneven playing field. “It’s what we do and have done since the beginning.”

—Amy Zavatto and Lana Bortolot

This post featured in our monthly newsletter from July 2022.

To get the latest from The Floating Hospital directly to your inbox, sign up using the form below. Other posts from this newsletter:

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Categories

Tags

The Floating Hospital provides high-quality healthcare to anyone who needs it regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, gender, immigration or insurance status, or the ability to pay. By providing unrestricted medical care in tandem with health education and social support to vulnerable New York City families, The Floating Hospital aims to ensure those most in need have the ability to thrive, not just survive.